The Jameson Raid

The early growth and development of Johannesburg was not without its periods of turbulence and violence. One of the earliest such crises was the Jameson Raid. This was the culmination of the activities of the Reform Movement started by a number of successful mining and business personalities in protest against what they felt to be the government's discriminatory attitude to the Uitlanders in Johannesburg, who had contributed in no small measure to the growth of the town. There appeared to be no attempt to solve these grievances by peaceful discussion or negotiations.

Finally the Reform Movement decided to attempt to over-throw the government by taking up arms. All this happened under the leadership of Dr Leander Starr Jameson, and became know as the Jameson Raid. It was launched on 29 December 1895 when Jameson and armed forces crossed the border from Bechuanaland. Jameson, however, had been too hasty, due to lack of communication and all telegraph lines were not cut as planned. AS a result the Boers received warning of the attack, and Jameson was forced to surrender on 2 January 1896 in Doornkop near Krugersdorp.

Braamfontein Dynamite Explosion

The dynamite explosion in the railway yards at the Braamfontein station, on the afternoon of 19 February 1896 was a tragedy that still ranks as the worst accident in the History of South Africa. Ten railway trucks loaded with more than 3 000 cases of blasting gelignite exploded with roar that was heard ten kilometres away. It carved a crater 75m long, 18m wide and 9m deep in the ground. Fragments of the trucks and other goods were blown over an area of 13 square kilometres. There is no certainty as to hown many were killed: reports vary from 78 to 130 and a few boxes of human remains. At least 300 people were injured, many of them seriously. The area around Newtown where old Johannesburg Market stands today, then known as the Brickfields, and a large area of Vrededorp were flattened and between two and three thousand people lost their homes. The explosion is said to have shattered every window in the centre of Johannesburg. The unidentified bodies were laid out at the Wanderers Club, and President Kruger, who came from Pretoria at the first new of the disaster, looked at the bodies of the children and wept.

|

| The explosion crater with work commencing on the edge - 19 February 1896 |

The Great Strike on the Rand

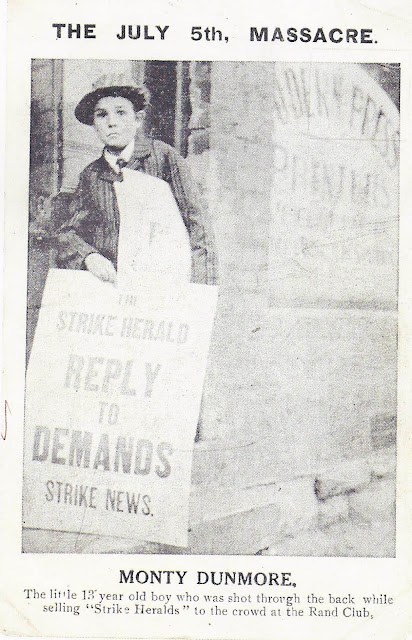

The years between the Union of South Africa and the First World War were ones of moderate prosperity. They were also years during which organised labour began to find its feet in the Union. The first trade unionists in South Africa were Uitlanders who came from overseas with long established traditions of trade union activities. By 1910 the trade unions had gained ground and were beginning to attract the uprooted Afrikaaners - the younger ones and those who failed on the land. These trade unions established among the men were, however, not recognised by their employers. Dissatisfaction grew among the miners on the Reef and culminated in an incident which arose from a little strike on the New Kleinfontein mine on the East Rand in May 1913.

The management refused to recognise this mining trade union and took on other men. This lead to a sympathetic strike in other mines. The government not realising the severity of the situation, took no steps to deal with the strikers' grievances, or to restrain them from violence until 4 July when a crowd of rioters set fire to the Park Station in Johannesburg, and 'The Star' offices there. Looting began almost immediately especially in jewellery and gunsmith shops, where the rioters were looking for firearm. The police opened fire which sparked further rioting and shooting in the town.

|

| The angry mob proceeded to set fire the 'The Star' offices |

Johannesburg's Demand for the Internment of Germans

Feelings against the Germans were running high during the First World War, especially after the sinking of the 'Lusitania' with the subsequent loss of many lives, and many German businesses and residences were being burnt. According to the records of the fire brigade, 65 fires were fought between 15h25 and 12h45 on 12 and 13 May 1915. Main Street, Johannesburg was reported to have been flowing with burning whisky from a nearby alcohol depot and in Newtown the large fodder warehouses smouldered for up to three weeks as a result of these anti-German riots.

|

| Gundlefinger's was an early business owned by a German Pioneer of the same name |